Glik Civil Rights Case Holding

A federal appellate court recent held that Maryland’s wiretapping statute could not be used to prevent citizens from recording police activity.

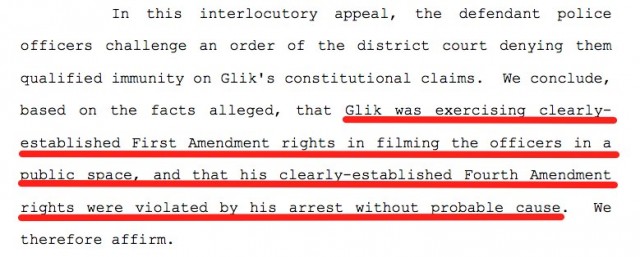

The abuse of this Maryland statute by police has been ripe for a challenge. When Simon Gilk was arrested for violating the statute because he was videotaping police in public view, he filed a civil rights suit against the officers and city for violating his First and Fourth Amendment rights. The officers attempted to get out of the case as named defendants because they claimed they had probable cause for the arrest. The court disagreed.

In the court’s opinion confirming the First Amendment right to videotape police in public places or when they come onto your property, the court noted the following:

Gathering information about government officials in a form that can readily be disseminated to others serves a cardinal First Amendment interest in protecting and promoting “the free discussion of governmental affairs.”

. . . .

This is particularly true of law enforcement officials, who are granted substantial discretion that may be misused to deprive individuals of their liberties. Ensuring the public’s right to gather information about their officials not only aids in the uncovering of abuses, but also may have a salutary effect on the functioning of government more generally. (citations to cases omitted).

And here’s the big holding that photographers who are not members of the press should pay specific attention to:

The First Amendment right to gather news is, as the Court has often noted, not one that inures solely to the benefit of the news media; rather, the public’s right of access to information is coextensive with that of the press. (my emphasis)

While this case is a First Circuit Court of Appeals case, the basic tenants of First Amendment case law cited by the court come from Supreme Court cases. As a result, photographers across the nation should feel a little better that this case has reached an appellate court and delivered this result.

Hopefully, this case will reach the desk of police chiefs across the US and will cause their departments to develop policies and training that acknowledges the fundamental right of any person to photograph or record police activity.

Silk’s civil rights case will continue because of this holding. Perhaps the city should have settled like Atlanta did earlier this year.

[via Slashdot]

Totally agree. No one, and that includes journalists and members of the public, have a right to expect privacy from visual capture in a public place – therefore they can also be recorded.

However, I would strongly argue that a person having a conversation in a public place in such a manner as to convey their desire that the conversation remain private, have the right to object to any audio recording of that conversation.

I would further argue that police have the right to seize any recording, be it visual or audio, on cellphone or DSLR, of any offence being committed for presentation as evidence to a court of law.

Be careful what you wish for… There is always an opposing argument.